1. Introduction

Transformers provide accurate short-term memory through attention but suffer from quadratic cost and fixed context window limits. Linear Transformers and modern linear RNNs improve efficiency but must compress all history into fixed-size states, which causes memory overflow and poor long-range recall.v

Human memory has separate short-term and long-term systems; existing architectures usually miss long-term memory that can adapt at test time.

Key question: How to design a neural long-term memory that can learn, forget, and recall information over extremely long contexts efficiently?

Titans introduce:

- A neural long-term memory (LMM) that updates weights at test time.

- Titans architectures that integrate LMM with attention and persistent memory.

2. Method

2.1 Neural Long-term Memory (LMM)

LMM treats learning as memorizing past tokens into its parameters during test time.

Uses a surprise metric: the gradient of the associative memory loss with respect to the input, larger gradient → more “surprising” token → more memorable.

The memory update dynamics are:

- Memory stores Associative key–value pairs using a loss**:**

$$ \ell = |M_{t-1}(k_t) - v_t|_2^2 $$

where $k_t = x_t W_K$ and $v_t = x_t W_V$.

- Surprise gradient:

$$ g_t = \nabla_{M_{t-1}}\ell $$

- Surprise momentum:

$$ S_t = \eta_t S_{t-1} - \theta_t g_t $$

- Combined using a data-dependent decay $\eta_t$ and learning rate $\theta_t$

- Forget gate: $\alpha_t \in [0,1]$

- $\alpha_t \to 1$ ⇒ forget history

- $\alpha_t \to 0$ ⇒ retain history

- Forget gate: $\alpha_t \in [0,1]$

- Memory update:

$$ M_t = (1 - \alpha_t) M_{t-1} + S_t $$

- Retrieval:

$$ y_t = M_t(q_t) $$

2.2 Parallelizable Training

LMM training is equivalent to mini-batch gradient descent with momentum + weight decay.

The authors show this can be reformulated into operations using matmuls + associative scan, enabling fast, hardware-friendly parallel training.

2.3 Persistent Memory

A small set of fixed, learnable vectors prepended to the sequence.

Purpose:

- Store task-level knowledge (not input-dependent).

- Counteract attention bias toward early tokens.

- Equivalent to data-independent attention keys/values (as shown by FFN→softmax reinterpretation).

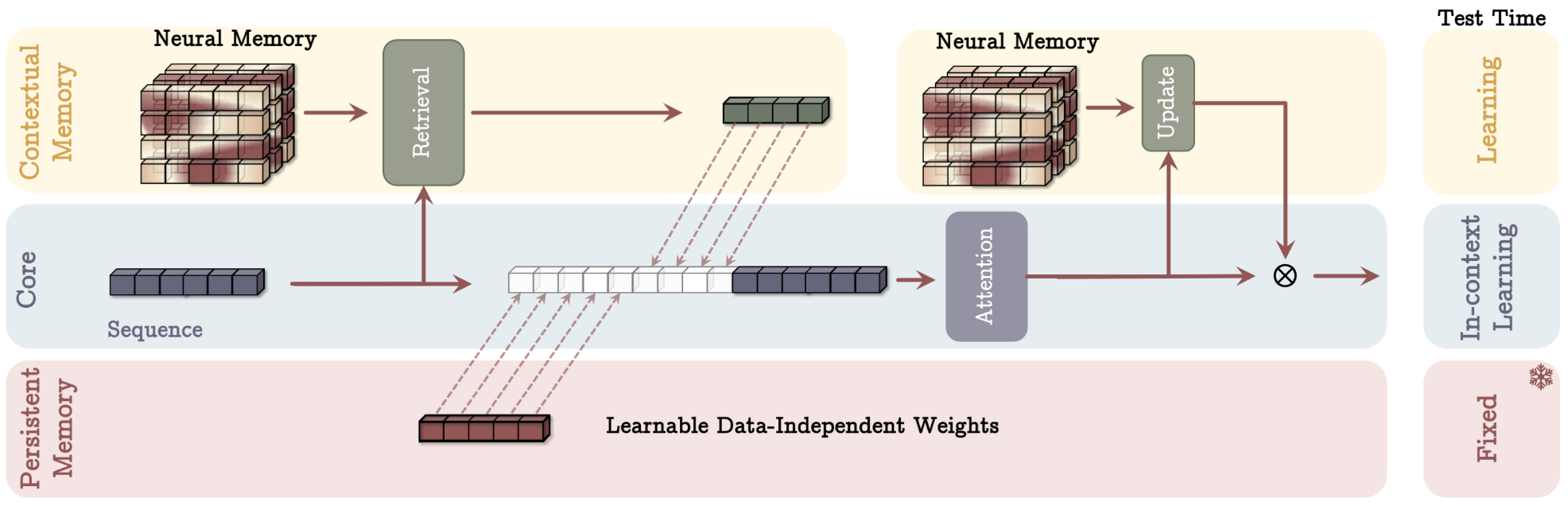

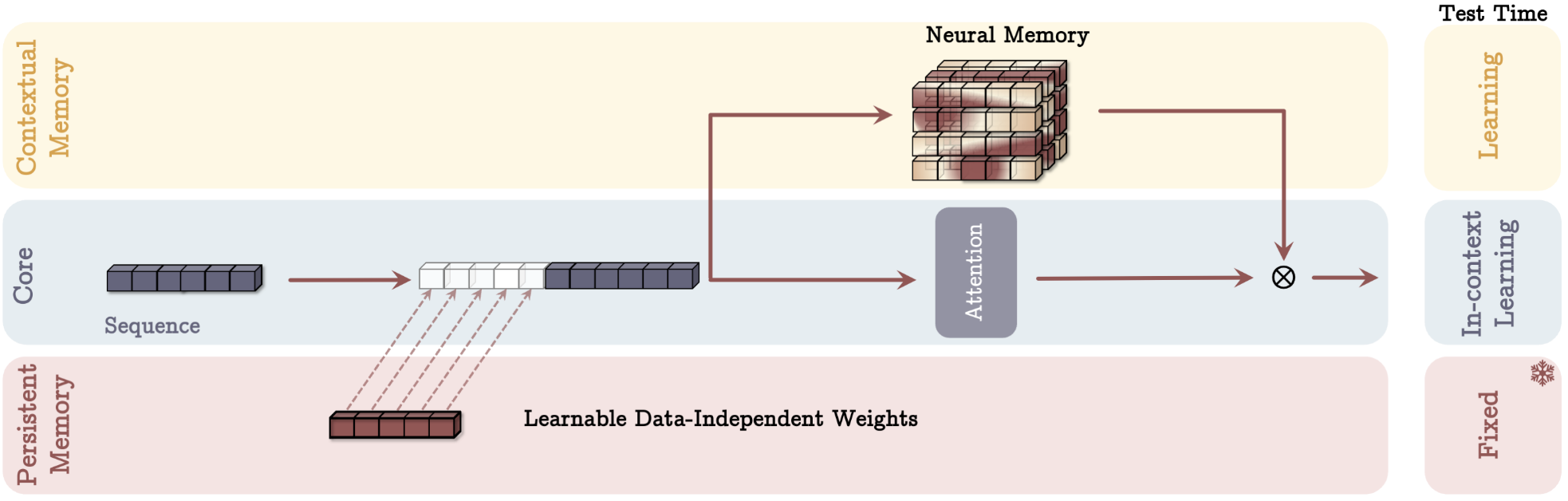

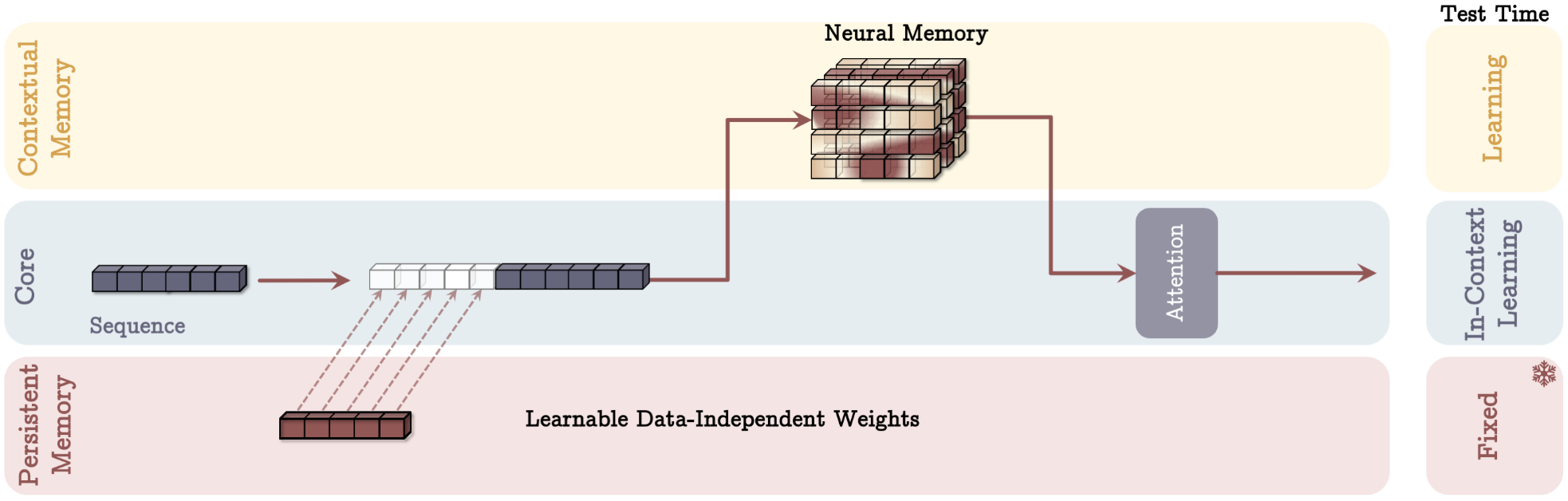

2.4 Titans Architectures (Three Variants)

All Titans have three components:

- Short-term memory = attention (sliding window attention)

- Long-term memory = LMM

- Persistent memory = learned prefix

Variants:

- MAC — Memory as Context:

Retrieve memory → concatenate with persistent memory → feed into attention → Best long-context performance.

- MAG — Memory as Gate: Combine Sliding Window Attention output and memory output via gating.

- MAL — Memory as Layer: Sequential: LMM → Sliding Window Attention. Simpler but weaker performance.

3. Novelty

3.1. Memory Structure

- Titans introduce a long-term memory (LMM) that can learn and store information across millions of tokens.

- This memory is a deep, learnable module, not just a matrix or KV-cache.

- Three designs (MAL) show flexible ways to combine long-term memory with short-term attention.

3.2. Memory Update

- LMM learns during inference, using a simple idea: more surprising tokens are written more strongly.

- Updates use momentum (past surprise + current surprise) for stability.

- A forget gate decides how much old memory to remove to avoid overflow.

3.3. Memory Retrieval

- LMM learns a key → value mapping, acting like a smart, compressing KV-cache.

- The model retrieves long-term information when needed and mixes it with short-term attention (SWA).

4. More Details

4.1. What is M?

M is a learnable function (an MLP) that stores long-term information.

$$ M : R^d \rightarrow R^d $$

It takes a vector (key or query) and outputs another vector (a “memory value”).

You can think of M as a neural dictionary:

- input = address

- output = content

Except this dictionary learns at test time, and compresses many past tokens into a fixed-sized neural network.

4.2. What does M do during RETRIEVAL?

Retrieval input: query

$$ q_t = x_t W_Q $$

Memory returns:

$$ y^{(LMM)}_t = M(q_t) $$

Meaning:

“Given this query, what long-term knowledge have we stored that matches it?”

So during retrieval:

- M behaves as a lookup function

- q = the question

- M(q) = the answer from long-term memory

Here, all the knowledge is compressed inside the MLP weights.

4.3. What does M do during UPDATE?

Update input: key

$$ k_t = x_t W_K,\qquad v_t = x_t W_V $$

Memory tries to learn the mapping:

$$ M(k_t) \approx v_t $$

Error:

$$ \ell = | M(k_t) - v_t |^2 $$

Gradient:

$$ g_t = \nabla_{M} \ell $$

Memory update:

$$ M \leftarrow M - \theta g_t $$

Meaning:

“Given this key, the correct value should be v. Update yourself so you can remember this in the future.”

So during update:

- M behaves as a learnable associative memory

- k = the address

- v = the content

- M learns: k → v

This is exactly like writing to a KV-cache — except the cache is a learnable neural network that can compress, forget, and generalize.

4.4. What role does M play?

Role 1: long-term storage

M learns from (k,v) pairs:

$$ M(k) \approx v $$

This is how it stores information.

Role 2: long-term retrieval

M responds to queries:

$$ M(q) = \text{long-term memory output} $$

This is how it retrieves information.

Why both? Because:

- Keys write into memory

- Queries read from memory

- Both must use the same space so they match