1. Problems

1.1. Multimodal action distributions

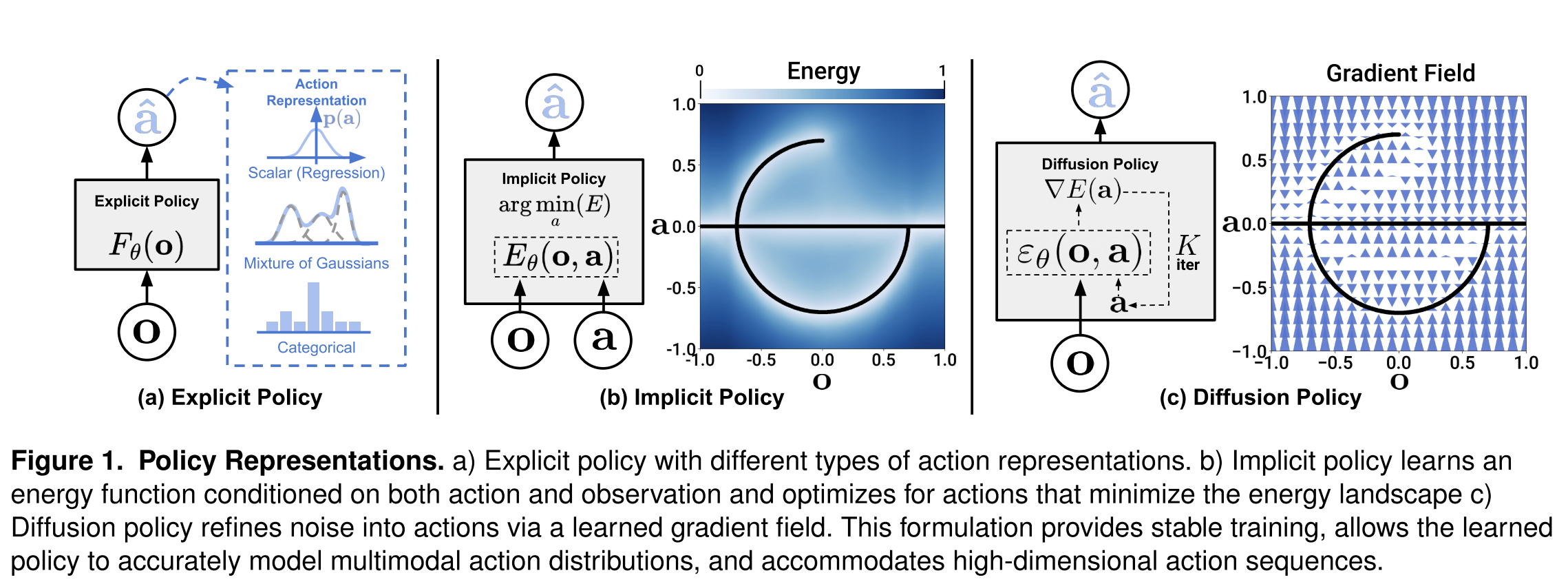

In demonstrations, the same visual/state observation can reasonably lead to different next actions (e.g., go left vs right around an obstacle, different grasp styles, different sub-goal order). Explicit regressions (single Gaussian / MSE) tend to average modes and become “invalid” actions.

1.2. High-dimensional output and temporal consistency

Robot control is sequential. Predicting one step at a time often produces tiny or mode-switching (action at t chooses mode A, action at t+1 chooses mode B). But predicting a whole action sequence is high-dimensional and hard for many policy classes.

1.3. Training instability of implicit / energy-based policies (IBC)

Implicit policies (IBC) represent $p(a|o)\propto e^{-E(o,a)}$ but training needs negative samples to estimate the intractable normalization $Z(o,\theta)$, which can be inaccurate and causes instability and checkpoint sensitivity.

1.4. Real-world deployment constraints

Policies must be fast enough for closed-loop control; naïve diffusion conditioning on both state and action trajectories can be expensive.

2. Method

Instead of outputting an action directly, the policy outputs a denoising direction field over actions and iteratively refines noise into an action sequence.

2.1. DDPM sampling view:

Start from Gaussian noise $x^K$. For $k=K\to1$, update (x → x - predicted noise + noise):

$$ x^{k-1}=\alpha\Big(x^k-\gamma,\varepsilon_\theta(x^k,k)+\mathcal N(0,\sigma^2 I)\Big) $$

where $\varepsilon_\theta$ is a learned “noise predictor” (can be seen as a learned gradient field).

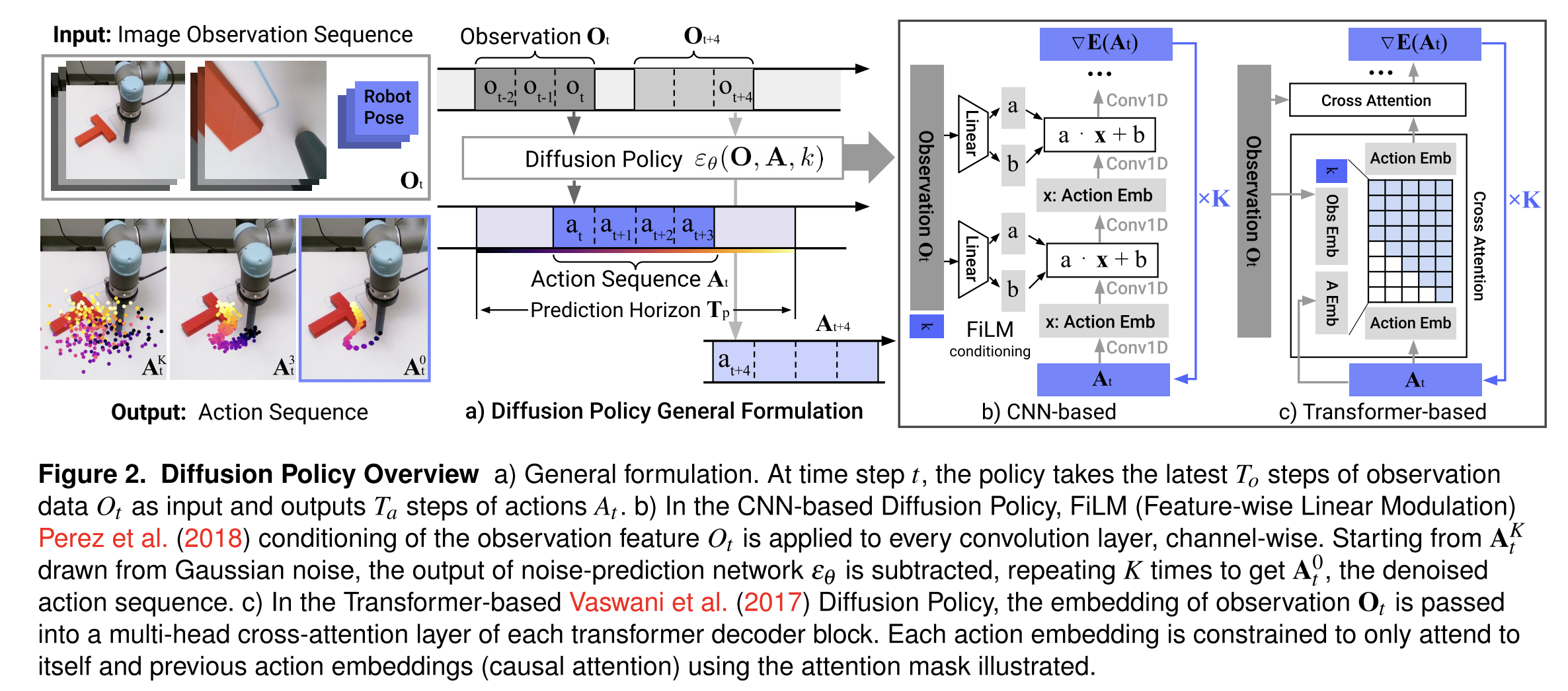

2.2. Adapt DDPM to visuomotor policy:

The denoising update becomes:

$$ A_t^{k-1}=\alpha\Big(A_t^k-\gamma,\varepsilon_\theta(O_t, A_t^k, k)+\mathcal N(0,\sigma^2 I)\Big) $$

So the network input is (observation features, noisy action sequence, diffusion step k) and output is predicted noise / denoising direction for that step.

2.3. Training:

Pick a clean expert action sequence $A_t^0$, sample a diffusion step $k$, add noise $\varepsilon_k$, train (actual noise added to the expert actions = predicted noise):

$$ L=\mathrm{MSE}\big(\varepsilon_k,\ \varepsilon_\theta(O_t,\ A_t^0+\varepsilon_k,\ k)\big) $$

This avoids EBM’s intractable $Z(o,\theta)$ and negative sampling.

2.4. Key technical contributions to make it work well on robots

Closed-loop action sequences + receding horizon control

At time $t$, use last $T_o$ observations $O_t$ to predict a future horizon of actions $T_p$, execute only $T_a$ steps, then re-plan (receding horizon). Warm-start the next plan for smoothness.

Visual conditioning for speed

Treat vision as conditioning: compute visual features once and reuse them across diffusion iterations, enabling real-time inference.

Time-series diffusion transformer

A transformer-based denoiser improves tasks requiring high-frequency action changes / velocity control, reducing over-smoothing seen in CNN temporal models.

- The expert trajectory contains: move → stop → move quickly → stop

- A CNN tends to produce: move → slow → slow → slow

Real-time acceleration via DDIM

Use DDIM(Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models) to reduce latency (reported ~0.1s on RTX 3080 for real-world). Train with many diffusion steps (e.g., 100), but infer with fewer (e.g., 10–16)

3. Novelty

3.1. New policy representation: “diffusion on action space”

They frame a visuomotor policy as a conditional denoising diffusion process over action sequences, not direct regression (explicit) and not energy-minimization with negatives (EBM).

3.2. Handles multimodality naturally via stochastic sampling + iterative refinement

Different random initializations $A_t^K$ and stochastic updates let the policy represent and sample multiple valid action modes, and action-sequence prediction helps it commit to one mode per rollout.

3.3. Scales to high-dimensional outputs by predicting action sequences

Diffusion models are known to work in high dimension; they exploit this to model whole trajectories, improving temporal consistency and robustness (including idle-action segments).

3.4. Training stability advantage over IBC/EBM

They explicitly explain stability: EBM needs $Z(o,\theta)$ and negative sampling; diffusion learns the score $\nabla_a \log p(a|o)$ which does not depend on $Z$, so training/inference avoid that source of instability.

3.5. System-level robotics contributions

Receding-horizon execution, efficient visual conditioning(Extract observations once, then reuse them across all diffusion steps), and a time-series diffusion transformer are concrete robotics-driven changes that “unlock” diffusion for real-world visuomotor control.