By the end of the Christmas holidays, I continued my VLA (Vision–Language–Action) learning track. I carefully read two papers: RT-1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale (Brohan et al., 2022 ) and RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control (Brohan et al., 2023 ) while writing my reading notes here: https://mrtanke.github.io/posts/2026-01-09-rt-series/ .

After finishing the notes, I decided to reproduce Robotics Transformer 1 (RT-1) in PyTorch, not to build a production system, but to truly understand the design decisions and implement the core ideas from the paper end-to-end. The goal is a learning-oriented, minimal implementation that stays close to the RT-1 architecture, while keeping the codebase clean and readable. Since training RT-1 at scale requires a heavy TFDS/RLDS pipeline and large real-robot datasets, I intentionally kept the data side minimal: I use a synthetic dataset that mirrors RT-1’s input and output shapes to validate the model forward pass, action tokenization, and the behavioral cloning training loop.

The repository is here: https://github.com/mrtanke/robotics-transformer

Core algorithm

The paper authors tried to answer a question: Can a transformer policy be large, general and still fast enough for real-time robot control? Obviously, the Robotics Transformer is based on the transformer framework (Vaswani et al., 2017 ) because transformer is a high-capacity sequence model, which makes it a natural candidate for learning general robot behaviours if we can train them on sufficiently large and diverse datasets. In original paper, it mentioned: The largest dataset for training contains over 130k individual demonstrations (trajectories) constituting over 700 distinct task instructions using a large variety of objects! That’s pretty impressive.

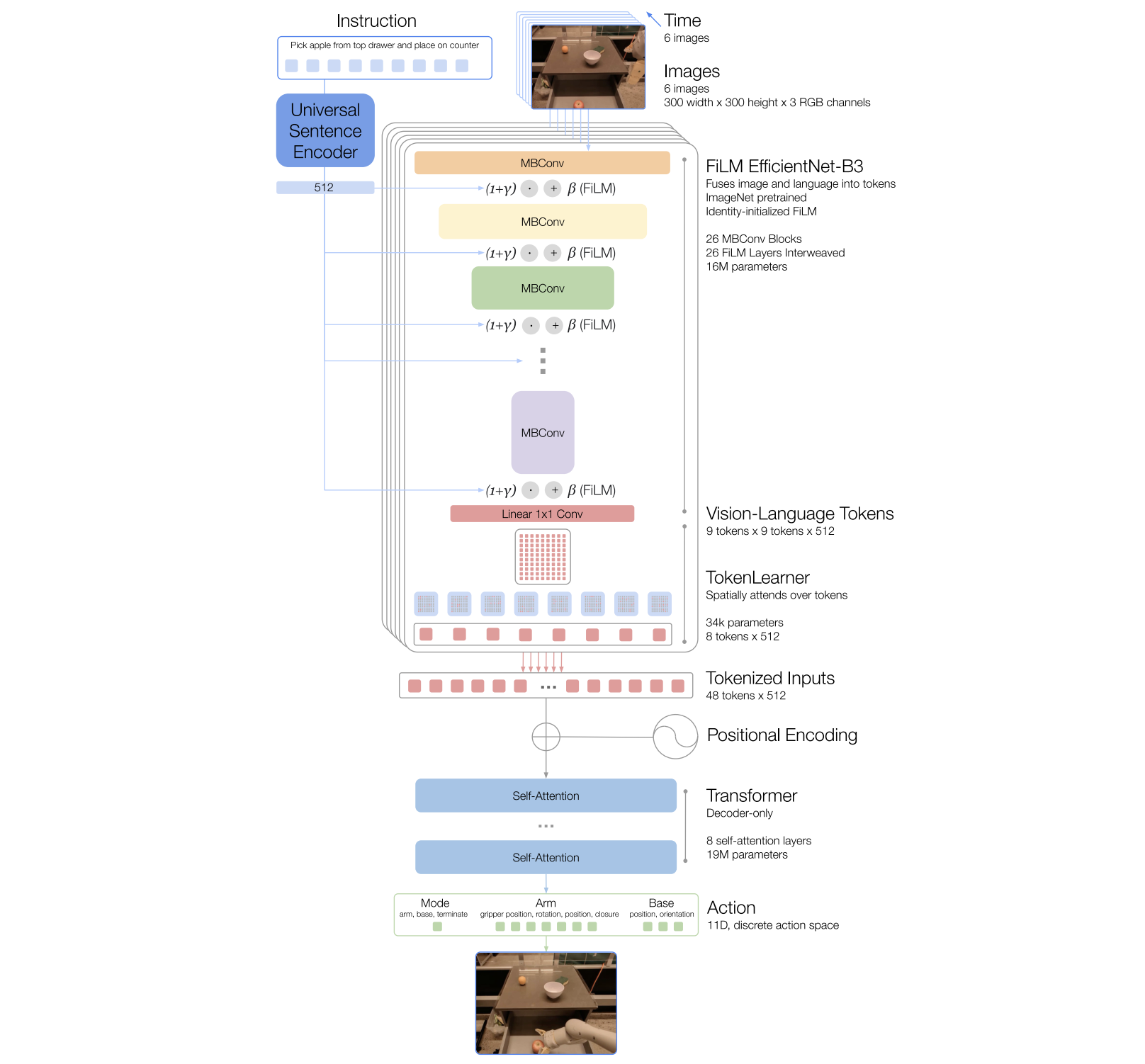

The challenge is speed. A naïve complete transformer over raw images and instructions would be far too slow for closed-loop control. RT-1 solves this by using a decode-only Transformer as the policy backbone. The model predicts the discretized action tokens with the fixed 256 bins per action dimension rather than continuous values, so the learning objectives become a straightforward classification problem. To speed up training, all the actions are generated in parallel in the causal attentions. Also, the input images and instructions are compressed to 8 tokens per image (via TokenLearner), and the Transformer input uses a per-timestep interleaved structure: [obs_1][act_1][obs_2][act_2]...[obs_T][act_T], where each timestep contributes 8 observation tokens + 11 action tokens = 19 tokens, for a total of 6 × 19 = 114 tokens. This is small enough to keep inference fast, and the images history can be reused.

The policy design of RT-1 follows the clean end-to-end VLA pipeline: the input images and intruction are fused as an embedding to feed into the Transformer, the tokenized actions are output. The training is a behaviour cloning process, minimizing the difference between the predicted action tokens and the demostrated action tokens.

Data

If we summarize the RT-1 work in one sentence, it would be : open-ended, task-agnostic training with a high-capacity model. So one of the key point is about data. A big Transformer policy only becomes general when it sees enough diverse knowledge. With a sufficiently broad dataset, the model can perform well on a new, specific task, sometime even zero-shot, or with only a small amout of task-speific data. So in RT-1, a huge part of the work is simply collecting and organizing data at scale.

In the paper, the authors use mobile manipulators from Everyday Robots , which have a 7 degree-of-freedom arm, a two-fingered gripper, and a mobile base. To collect demonstrations and evaluate the method, they run experiments in three kitchen-based environments: two real office kitchens, plus a training environment modeled after them. The scale is impressive, the largest dataset includes 130k individual demonstrations (trajectories) covering over 700 distinct task, with a wide variety of objects.

For my reproduction, I’m deliberately not trying to fetch and preprocess the full RT-1 dataset, which would mean spending a lot of time dealing with TFDS/RLDS pipelines….. Instead, I focus on validating the core model pipeline with a minimal but shape-faithful dataset. So I implemented a SyntheticRTDataset as a PyTorch IterableDataset, which plugs directly into a DataLoader. Each training sample follows the RT-1 “contract”: 6 history images + 1 instruction embedding + 11 discretied action dimensions. I skip the instruction embedding directly. This matches the workflow in the official implementation

, where the dataset already provides instruction embeddings rather than raw text.

A single sample has the following shapes:

images:(history_len, 3, image_size, image_size)instruction_emb:(instruction_dims,)action_tokens:(action_dims,)— the target for the current timestepaction_tokens_history:(history_len, action_dims)— ground-truth actions for all T timesteps in the history window

The default settings live in the class RoboticsTransformerConfig:

history_len = 6image_size = 300instruction_dims = 512action_dims = 11action_bins = 256- …

Next, I’ll walk through the implementations and how shapes flow through action tokenization, visual tokenization, TokenLearner, and the causal Transformer decoder.

Repo Skeleton

robotics-transformer/ # repo root

├── robotics_transformer/ # main python package (the RT-1 reproduction)

│ ├── configs/

│ │ └── default.py # default hyperparams (shapes, horizons, model sizes...)

│ ├── data/

│ │ ├── windowing.py # build history frames training windows

│ │ └── synthetic_dataset.py # generates lightweight RT-style batches without external data

│ ├── tokenizers/

│ │ ├── action_bounds.py # default per-dimension bounds for actions

│ │ └── action_tokenizer.py # continuous action <-> discrete tokens

│ ├── models/ # RT-1 core architecture blocks

│ │ ├── film.py # FiLM conditioning (instruction -> modulate vision)

│ │ ├── film_efficientnet_b3.py # EfficientNet backbone with FiLM layers

│ │ ├── token_learner.py # TokenLearner compression (many tokens -> few tokens)

│ │ ├── transformer_decoder.py # decoder-only causal transformer

│ │ └── policy.py # RT1 policy module wiring everything together

│ └── training/

│ ├── trainer.py # minimal training entry

│ ├── losses.py # cross entropy loss for action token prediction

│ └── trainer.py # train/eval loop, logging, checkpointing

├── scripts/

│ ├── smoke_test_dataset.py # verify dataset yields correct shapes/dtypes

│ ├── smoke_test_forward.py # verify model forward logits shape

│ └── smoke_test_trainbc.py # verify train_bc function

├── tests/ # unit tests

│ ├── test_action_tokenizer.py # discretization correctness + bounds

│ ├── test_token_learner_shapes.py # TokenLearner input/output shapes

│ ├── test_transformer_causal_mask.py # causal masking sanity checks

│ └── test_rt1_forward_shapes.py # end-to-end forward shape contract

└── train.py # repo-level training entrypoint (thin wrapper)

Implementation Steps

According to the RT-1 architecture diagram, I break the model into three main components: (1) image + instruction tokenization, (2) TokenLearner, and (3) the Transformer policy backbone. On top of that, RT-1 places special emphasis on action tokenization, turning continuous robot controls into discrete tokens, so the whole control problem can be expressed naturally in a Transformer-style sequence modeling framework.

At the end of the day, RT-1 is still a VLA model: in control theory and reinforcement learning terms, a policy is simply a function that maps a state (observations + instruction) to an action. In this repo, I implement a Policy module that integrates all of these pieces into one clean forward path: observations and instructions go in, and tokenized (then decodable) actions come out.

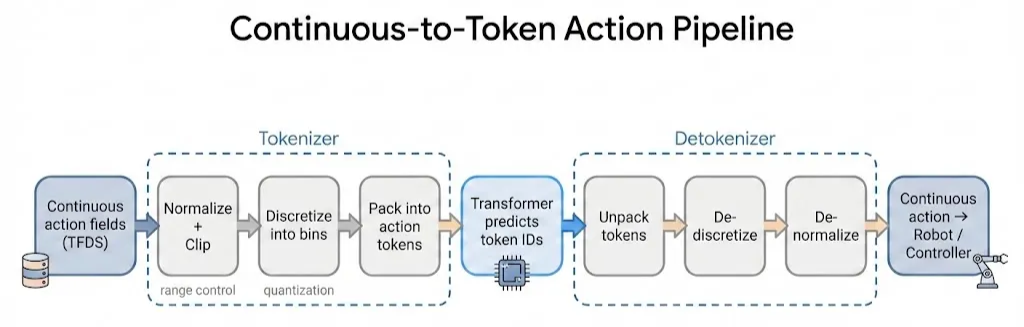

1. Action tokenization

In the official TensorFlow RT-1 repository, each action from the dataset is represented as an 11-dimensional continuous vector: 3D translation (world frame), 3D rotation, 1 gripper command, 3 base commands and 1 discrete mode (arm / base / terminate).

Before feeding actions into the Transformer, RT-1 applies a standard pipeline: normalize + clip, then discretize each dimension into 256 bins. The clip ranges differ by dimension, so each action component has its own bounds.

The overall pipeline looks like this:

Following the official implementation, I define two core functions: encode and decode in action_tokenizer.py.

encode(continuous → tokens)- clamp each dimension to its

[low, high]range - for continuous dimensions: apply uniform binning into integers in

[0, num_bins - 1]; for the mode dimension: round to the nearest integer in{0, 1, 2} - return the resulting integer action tokens

- clamp each dimension to its

decode(tokens → continuous)- for continuous dimensions: map token IDs in

[0, num_bins - 1]back to continuous values in[low, high](typically using bin centers); for the mode dimension: keep it as an integer in{0, 1, 2} - return a reconstructed continuous action vector

- for continuous dimensions: map token IDs in

In my repo, the synthetic dataset already produces discretized action tokens, so encode is not strictly required for training. But I still implement both encode and decode to match the official RT-1 design and to keep the action interface complete.

2. Image tokenization

I implement a minimal FiLM-conditioned EfficientNet-B3 tokenizer. It takes an RGB image and an instruction embedding as inputs, and produces a compact set of vision–language tokens for the policy.

FiLM (Shen et al., 2017

) stands for Feature-wise Linear Modulation. Given an activation tensor x, FiLM applies an affine modulation conditioned on the instruction embedding:

$$ y = (1 + \gamma)\odot x + \beta $$

A small but important detail from RT-1 is the identity initialization: at the very beginning of training, we want FiLM to behave like a no-op so we don’t destroy the pretrained EfficientNet features. In practice, this means initializing the FiLM generators so that γ = 0 and β = 0 at start, making $y \approx x$. As training progresses, the model learns how to modulate visual features based on the instruction.

Here is the core forward pass of the FiLMEfficientNetB3Tokenizer:

def forward(self, images: torch.Tensor, text_emb: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

images: (B, 3, H, W)

text_emb: (B, instruction_dim)

returns: (B, 81, token_dim)

"""

x = images

for stage, film in zip(self.stages, self.films):

x = stage(x)

x = film(x, text_emb)

x = self.proj(x) # (B, token_dim, h, w)

x = self.pool(x) # (B, token_dim, 9, 9)

return self.flatten_tokens(x) # (B, 81, token_dim)

3. TokenLearner

TokenLearner’s job is to compress a large token set into a small, informative subset. In RT-1, feeding all 81 tokens from each frame into the Transformer would be expensive, especially with a 6-frame history. TokenLearner solves this by reducing 81 → 8 tokens per image. Conceptually, TokenLearner learns M “soft selection” masks over the N input tokens. There are N = 81 input tokens, M = 8 output tokens, each output token is a weighted sum of the original 81 tokens. So for each output token $m$, the model predicts attention weights $w_{i,m}$ over all input tokens $i$, then aggregates them:

$$ \text{output}_m = \sum_{i=1}^{N} w_{i,m} \text{token}_i $$

In code, this is exactly what happens:

def forward(self, tokens: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

tokens: (B, N, D) # N=81, D=token_dim

returns: (B, M, D) # M=8

"""

attn = self.mlp(tokens).softmax(dim=1) # (B, N, M)

# (B, M, N) @ (B, N, D) -> (B, M, D)

return torch.matmul(attn.transpose(1, 2), tokens)

A small detail that matters: the softmax(dim=1) normalizes across the token dimension N, so each of the M output tokens forms a proper distribution over the 81 inputs. The final matmul is just a batched weighted sum, producing 8 learned summary tokens that preserve task-relevant information while keeping the Transformer input short and fast.

4. Transformer

RT-1 uses a decoder-only Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017 ) as its policy backbone. In my implementation, the Transformer module is kept minimal: add positional embeddings, run a stack of decoder blocks (each block = causal attention + MLP with residual connections), and finish with a final LayerNorm:

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

x = x + self.pos_emb[:, :T, :]

x = self.blocks(self.drop(x))

return self.ln_f(x)

5. Policy Integration

I wrap the whole RT-1 pipeline into a single robotic_transformerPolicy module. Given a 6-frame image history and a 512-d instruction embedding, the policy first tokenizes each frame with a FiLM-conditioned EfficientNet-B3 to produce 81 tokens per frame, then compresses them with TokenLearner to 8 tokens per frame.

Following the official implementation, the Transformer input uses a per-timestep interleaved concatenation rather than a single merged [obs][act] block. Each timestep contributes its own [obs_t][act_t] group (8 + 11 = 19 tokens), and the full sequence is:

$$ [\text{obs}_1][\text{act}_1][\text{obs}_2][\text{act}_2]\dots[\text{obs}_T][\text{act}_T] $$

with $T \times 19 = 6 \times 19 = 114$ total tokens. During training, past action tokens (timesteps 1 to T−1) are ground-truth context, and the current timestep’s action tokens are teacher-forced (BOS + shifted target) so the model can predict all 11 action tokens in parallel under the causal mask.

For inference, a simple autoregressive generate_action_tokens() loop builds the past context [obs_1][act_1]...[obs_{T-1}][act_{T-1}][obs_T] once, then samples the 11 action tokens step by step from the Transformer’s output distribution.

Training

For training, I keep everything as simple as possible and treat RT-1 as a behavior cloning problem on discretized action tokens. Each batch provides images (6-frame history), instruction_emb (512-d), action_tokens_history (per-timestep ground-truth actions for the interleaved context), and action_tokens (11 target integers for the current timestep). The policy outputs logits of shape (B, 11, 256), and training minimizes a standard cross-entropy loss between predicted logits and the ground-truth action tokens. The training loop uses AdamW, applies gradient clipping for stability.

Since the dataset is synthetic, the goal here isn’t to reach meaningful real-world performance, it’s to verify that the full pipeline (tokenizers → transformer → loss) is wired correctly and can train end-to-end without shape or masking bugs.

Over

Embodied intelligence and vision-language action are moving incredibly fast. RT-1 is only a few years old, but in this field that can already feel “outdated”. Still, I think RT-1 is genuinely instructive, because it shows a clean and scalable recipe for robot learning: tokenize observation efficiently, discretize actions to make control a sequence problem and train a high-capacity Transformer policy with behavior cloning. These design principles keep showing up again and again.

For me, this reproduction is less about chasing the newest benchmark and more about building solid intuition: understanding the data contract, the tokenization choices, and the engineering trade-offs that make real-time control possible.

And yes, there’s still a long way to go. I’ll keep pushing, keep building, and keep improving step by step!

References

- Brohan, A., Brown, N., Carbajal, J., et al. RT-1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale. arXiv:2212.06817, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.06817

- Brohan, A., Chebotar, Y., Finn, C., et al. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. arXiv:2307.15818, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.15818

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., et al. Attention Is All You Need. NeurIPS, 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

- Perez, E., Strub, F., de Vries, H., et al. FiLM: Visual Reasoning with a General Conditioning Layer. AAAI, 2018. (preprint: arXiv:1709.07871) https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.07871

- Everyday Robots. Everyday Robots (robot platform / project site). https://everydayrobots.com/

- Google Research. Official RT-1 TensorFlow implementation (archived). https://github.com/google-research/robotics_transformer

- Ke Tan (mrtanke). RT series reading notes. https://mrtanke.github.io/posts/2026-01-09-rt-series/